Questions About FBI Surround Case of Murdered Police Chief

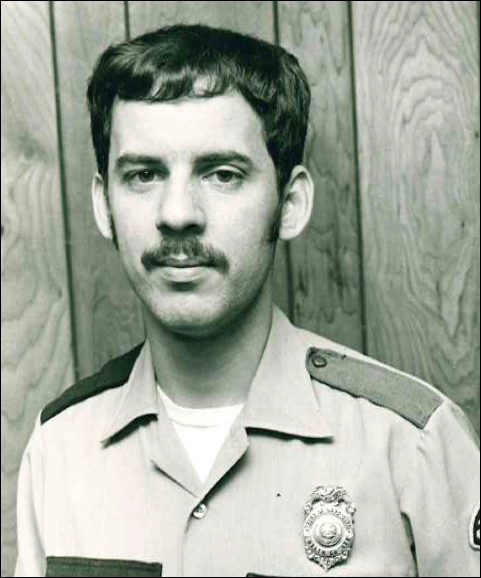

On a December day in a small Pennsylvania town in 1980, a fugitive jewel thief murdered the police chief and vanished. The thief was a New England career criminal named Donald Eugene Webb. The chief was Gregory Patrick Adams, a former Marine and city cop who took the Pennsylvania job in search of quieter times. Webb went on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted” list and a thirty-seven-year manhunt of sorts ensued.

Last year, it ended. Webb’s remains were dug up in his wife’s back yard.

Her name is Lillian Webb. According to the FBI, her husband died around 1999 and Lillian buried him behind her home in North Dartmouth, Massachusetts, out by an old shed.

He remained there until 2017, when mysterious developments suddenly breathed new life into the case. But the biggest mystery of all is how Donald Webb eluded capture for nineteen years.

Documents reviewed by Judicial Watch suggest that most of the time — perhaps all of the time — he was living with Lillian. The documents raise new questions about Webb, the FBI, and the murder of Chief Adams. How did one of America’s most-wanted fugitives hide out for nearly two decades in his own home, right under the FBI’s nose?

FALL RIVER GANG

By the time of the Adams murder, Webb had a rap sheet going back twenty-five years. Law enforcement sources say he was an associate of the Fall River Gang, a loose confederation of criminals based in southeastern Massachusetts and specializing in burglaries of high-end homes and jewelry stores. The stolen goods allegedly were fenced through New England’s dominant Mafia group, the Patriarca crime family. But much remains murky about the true shape of the Fall River Gang and Webb’s Patriarca connection.

Investigators believe Webb was in tiny Saxonburg, Pennsylvania, casing a jewelry store when something caught Chief Adams’s attention. The chief, in his patrol car, pulled up to Webb’s rented white Mercury Cougar in an Agway parking lot. Webb had done prison time and was wanted in New York for burglary. He had told associates he wasn’t going back to jail.

He must have come at Adams fast. “The chief was shot twice at close range after being brutally beaten about the head and face,” the FBI noted its “Wanted” bulletin. The murder weapon, a .25 caliber handgun, was recovered at the scene. Adams’s .38 was missing.

But it was clear that Adams had fiercely fought back. Webb was injured. A witness reported seeing Webb limping in the parking lot, his leg bloody. He left a blood trail from Adams’s cruiser back to where his Cougar had been parked.

The killer was calculating. He tore the radio handset from the police cruiser and a bloody notebook was missing the top page. Blood was found on the door, armrest, and steering wheel of the cruiser.

The Cougar was quickly located in a parking lot in Rhode Island. A driver’s license found at the crime scene linked both Donald and Lillian Webb to the car. The license used in renting the car was issued to Stanley Portas, the first husband of Lillian Webb, long dead. Earlier that year, Lillian had cashed a refund check from a car rental company for a different vehicle rented under the Portas alias. The same type of blood found at the crime scene was found in the Cougar.

Less than two weeks after the murder, police were closing in. They’d identified a suspect (Webb) and linked his wife (Lillian) to the Portas alias. Due to the amount of blood at the crime scene that did not belong to Adams — his blood type differed from Webb’s — investigators believed Webb had been shot in the struggle and would be seeking medical help.

Then Webb disappeared.

What happened to Webb the day of the shooting, and the following weeks, is one of the mysteries of the case. The FBI has not released autopsy results for Webb. According to an account that emerged decades later, Chief Adams in fact had not shot Webb in the struggle, but had badly beaten him, tore his lip and broke his leg.

According to a recent police report on the case, Webb checked into a Massachusetts hospital after fleeing Pennsylvania and remained there for a month, under an alias.

It seems astonishing that a wounded cop killer could escape notice by checking into a hospital under a false name. But investigators associated with the case note that police would have been looking for someone with a bullet wound, not a broken leg. And yet, Webb’s other wounds likely would not have gone unnoticed.

The tightly knit towns around Fall River may have given Webb additional protection. According to an affidavit submitted by Pennsylvania’s lead investigator in the case, when the commanding officer for the Massachusetts State Police in the Fall River area learned that “the Pennsylvania State Police and FBI were actively looking for Webb in regards to the murder of a police officer,” he called Lillian and told her.

The commanding officer “had previously been acquainted with Lillian,” the document noted. “Lillian, and likely Webb, thus were notified that Webb had been identified as the murderer of Chief Adams, before law enforcement was physically able to locate Webb.”

Was the FBI also acquainted with the Webb family? No evidence links the FBI to Donald Webb in the years prior to the killing of Chief Adams. But plenty of evidence has emerged over the years connecting the FBI’s troubled Boston field office to members of organized crime in New England. Donald Webb allegedly was connected to some of the same mobsters.

By 1980, the time of the Adams killing, members of the FBI’s Boston office had become deeply enmeshed in a corrupt relationship with New England gangsters. FBI agents John Morris and John Connolly committed crimes with organized crime figure Whitey Bulger, paving the way for Bulger’s takeover of Boston’s Winter Hill Gang.

In Providence, mobster Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi had provided the FBI with detailed information about the Patriarcas. Flemmi later migrated up to Boston and became involved with Bulger and his FBI handlers. Protecting their informants, the FBI was drawn into a web of murder and racketeering by Bulger and Flemmi.

The Bulger case was a body blow to the Boston FBI. FBI agent John Connolly was convicted of murder and racketeering. FBI agent John Morris was granted immunity for his testimony against Connolly. Bulger and Flemmi were sentenced to life in prison for multiple acts of murder and racketeering. Read more about the case here.

LILLIAN WEBB

Lillian Webb immediately came under suspicion of harboring her fugitive husband. We know that from the rental car links to “Stanley Portas” and police attempts to interview her in the early days of the investigation. She refused law enforcement interview requests and referred all inquiries to her attorney.

According to the affidavit filed in the case by Pennsylvania investigators, in the early years of the manhunt, the FBI noted that “Lillian routinely engaged in evasive driving techniques” while under FBI surveillance. “Additionally, Lillian was known during this time period to routinely wear wigs and change her hair color, in an attempt to evade law enforcement.”

In the 1990s, the FBI reportedly installed a camera across the street from Lillian’s residence. The camera revealed that “Lillian would always pull into her garage in a suspicious manner. Lillian would utilize an electric garage door opener and never exit her vehicle upon entry,” instead waiting for the garage door to close before coming out of the car.

In 2016, the FBI turned up the heat. It offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to Webb’s arrest — or his remains. He would have been 84 at the time.

At the same time, the Massachusetts State Police ramped up an investigation into Donald and Lillian Webb’s son, Stanley, for running an illegal gaming operation.

In November 2016, the FBI obtained a warrant and searched Lillian Webb’s home. That warrant is part of the puzzle of the case. The basis for the warrant is unclear. The FBI and district court have not released the underlying documents supporting the search petition. The cover page of the warrant indicates that the FBI was looking for evidence to support a false statements charge.

Evidence seized in the search was scant, according to the FBI property receipt: a few photographs and two driver’s licenses.

But FBI search did lead to one startling discovery: a secret room in Lillian Webb’s basement.

“The hidden room was about the size of a large shower stall,” a police document reported. “There was a hook lock fastened to the inside of the door of the hidden room”. The only rational purpose of this hook lock was for a person to lock the door after entering the room.” Inside the room was “a walking cane and three cardboard boxes of silver coins.”

The Massachusetts State Police followed up on the FBI search with a warrant application of their own. The investigator behind that warrant application worked for the Massachusetts attorney general’s Gaming Enforcement Division, which was running the Stanley Webb gambling probe. But the application appeared to have little to do with that investigation. They were after Donald.

The Massachusetts warrant sought permission to search Lillian Webb’s home for the body of Donald Webb, evidence that he had lived there, and any evidence that would “assist investigators in identifying other co-conspirators associated with the murder of Chief Adams.”

The FBI’s discovery of the secret room also caught the attention of a family in Pennsylvania. Chief Adams has left behind a wife and two young sons. They launched a wrongful death lawsuit against Donald, Lillian, and Stanley Webb. The charges were murder, “accessory after the fact” of murder, and “hindering apprehension of a murderer.”

For Lillian, the jig was up. It was time to talk. Her attorney was Jack Cicilline, the longtime lawyer for New England crime boss Raymond Patriarca. Cicilline cut an immunity deal, including protection from the Adams family’s civil suit.

In July 2017, Lillian gave a lengthy statement to investigators from the FBI, the Pennsylvania State Police and the Massachusetts State Police.

Lillian said that Donald Webb had told her about the murder of Chief Adams. The chief put up a ferocious battle, Lillian said, breaking her husband’s leg and tearing his lip. Webb fled back to New England and Lillian helped him dispose of the rental car.

After a month in the hospital, Lillian told investigators, Webb came to their home in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She indicated he lived there, and at their subsequent home, for the next nineteen years. The earlier home also contained a hidden room, investigators believe.

Lillian said that on occasion over the years, she would take Webb out in her car, with him stretched across the back seat to avoid detection.

In 1997, she purchased the home in North Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Soon after, Lillian told investigators, Webb had a stroke. According to an affidavit supporting the Massachusetts search warrant application, soon after the stroke, Webb informed his wife “that he was dying and instructed her to begin digging and prepping a hole in the back yard to bury him.” Sometime between 1997 and 1999 — both years are cited in the documents and news reports of the case — Webb had a second stroke and died.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

Last month, Massachusetts brought the hammer down on Stanley Webb. He and his daughter and son-in-law were indicted for running an illegal gambling operation.

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey called it the dismantling of a “major criminal enterprise.” But the case, revolving around vending machines where customers try their luck in winning pre-paid phone cards or store credit, hardly seems like a major blow against organized crime. And there is the curious intersection of FBI and Massachusetts search warrants in the case. It’s reasonable to wonder if the Massachusetts charges were ginned up to leverage the Webb family to open up about Donald Webb’s whereabouts.

Other questions also remain as well.

Did Donald Webb really evade capture for nineteen years by hiding all that time in his own home? Can Lillian Webb be believed?

And what about the FBI? There’s no hard evidence that Webb was a protected informant for the FBI, similar to Bulger or Flemmi, or that he enjoyed a special relationship with the Massachusetts State Police. But some New England law enforcement figures think Webb may have been informing on Patriarca crime family activities, particularly its fencing operations for the Fall River Gang — making him a valuable FBI asset.

It appears that the FBI had plenty of probable cause to obtain a search warrant for the Webb residences in the early years of the investigation — Lillian’s evasive actions, the Stanley Portas alias connection to the car rentals, her refusal to cooperate with investigators — and did not. Why not?

Upcoming developments may shed light on the case. Judicial Watch is seeking documents related to Webb’s activities and Lillian’s statements to investigators. Stanley Webb’s gambling trial may open doors into the FBI and Massachusetts State Police investigations. And as for that wrongful death civil suit brought by the family of Chief Adams, a lawyer for the family pointedly told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that the immunity deal negotiated by Lillian Webb’s lawyer applied only to her. “We had no deal with Stanley,” he said.

Stay tuned.

***

Micah Morrison is chief investigative reporter for Judicial Watch. Follow him on Twitter @micah_morrison. Tips: mmorrison@judicialwatch.org

Investigative Bulletin is published by Judicial Watch. Reprints and media inquiries:Â jfarrell@judicialwatch.org